Just one day after the U.S. military raid in Venezuela and the arrest of President Maduro, an announcement from South Korea has shed light on Venezuela's unique role in the global geopolitical chessboard.

Korea Zinc unexpectedly announced a strategic partnership with U.S. partners to build a smelter complex in Clarksville, Tennessee. The surprise isn't just the massive $7.4 billion investment. It marks a historic turning point: the first time the U.S. government has directly intervened in the ownership structure of a civilian heavy industry project.

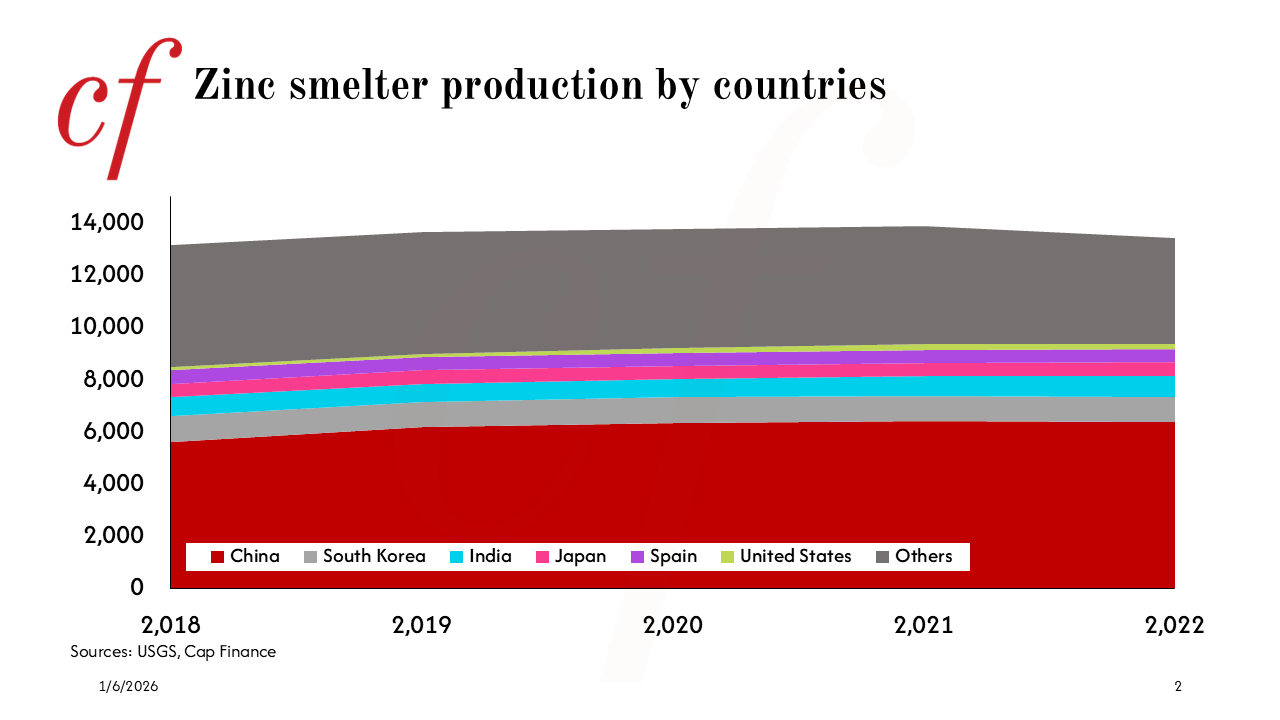

With the U.S. Department of Defense as a shareholder, alongside the powerful financial institution JPMorgan, this facility is clearly more than a commercial venture. It is a key national security asset. This announcement effectively declares the end of an era where the U.S. left metal supply chains to the free market, signaling a shift toward centralized control and absolute protection on its own soil.

Technically, the plant's real value lies in Korea Zinc's proprietary "fully integrated smelting" technology—something U.S. industry lost long ago. Unlike traditional smelters that isolate one metal and discard the rest, this system acts as a sophisticated "omnivore," capable of processing the planet's most complex polymetallic ores.

It can extract 13 different elements from a single block of raw ore, recovering everything from zinc, lead, and copper to precious metals like silver and gold, and crucially, strategic rare metals like Indium and Gallium for semiconductors. The ability to process "dirty" and complex ores with near-perfect recovery rates is the key factor defining the supply strategy for this complex.

The urgent need for this technology comes from a harsh reality: the U.S. is being strangled by its dependence on Chinese processing capacity. For decades, the U.S. accepted a "dig and ship" model, sending raw ore to Asia for refining and buying back finished products at a premium, all while risking supply cuts.

As silver and zinc become vital for the green energy transition and defense industry, lacking a domestic smelter means the U.S. has the rice but cannot cook the meal. The Tennessee plant is Washington’s "all-in" solution to cut out the Chinese middleman, ensuring that resources mined in the Western Hemisphere are processed and consumed within the region.

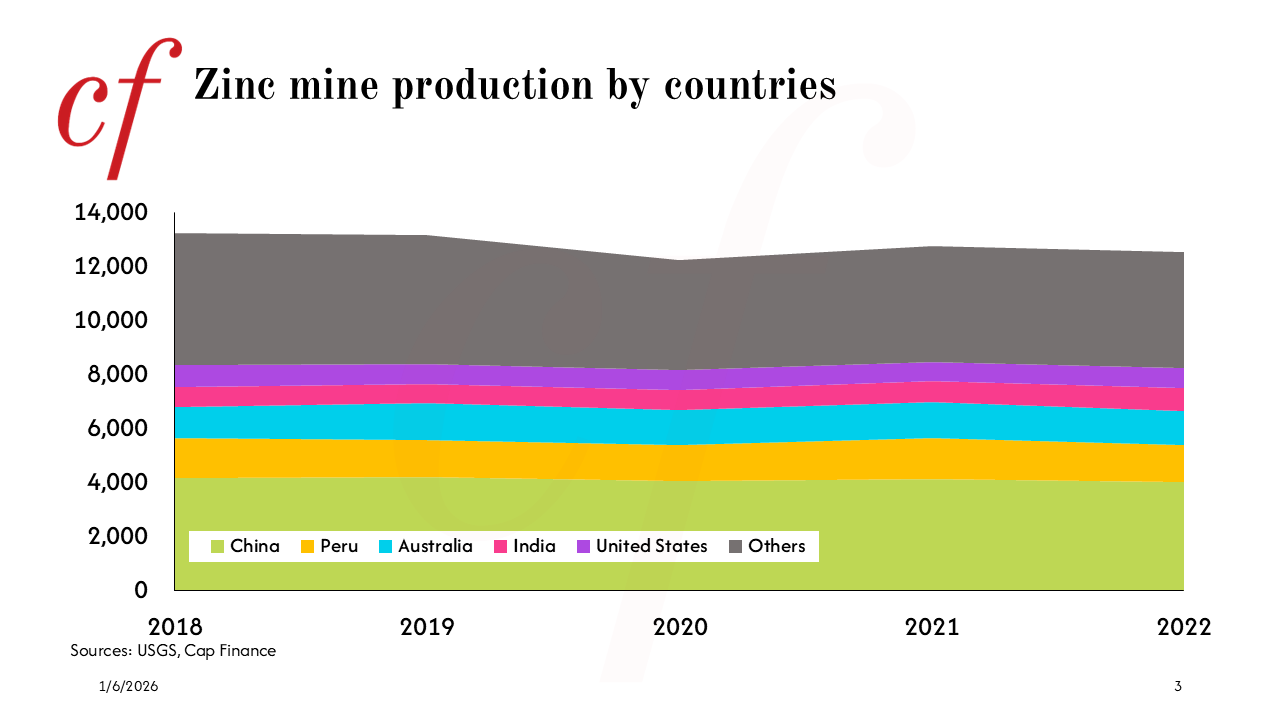

Technical requirements for processing polymetallic ore and the geopolitical mandate for a closed supply chain have led directly to Latin America's mineral wealth. Geologically, the American Cordillera—running from the massive silver mines of Mexico down to the zinc hubs of Peru and Bolivia, and extending to the Venezuelan Andes—is the only place on earth providing large-scale complex sulfide ores. These are the perfect "feedstock" to optimize the Korea Zinc smelter.

Instead of processing expensive single-metal ores from Australia or Canada, importing mixed ores from South America allows the plant to maximize metal recovery, turning impurities into net profit. Furthermore, shipping from South American ports directly into the Gulf of Mexico to reach Tennessee is far shorter and safer than the risky trans-Pacific route.

Evidence for this tight link is becoming clearer through capital movements and asset ownership structures. The Clarksville site was originally owned by Nyrstar, a subsidiary of the commodity trading giant Trafigura—a "kingpin" controlling numerous major mines in South America.

Building the plant on Trafigura’s foundation means inheriting an established logistics system and raw material supply from Latin America. At the same time, JPMorgan's aggressive moves—funding the project while quietly hoarding massive amounts of physical silver—are a clear signal. They are positioning themselves to catch the flow of high-value precious metals that will be extracted from these South American ores.

understand that the U.S. cannot allow an untapped mineral reserve in its own backyard to fall into Beijing's crosshairs. Securing Venezuela now is a calculated preemptive strike: rehabilitating its dormant zinc and silver mines during the three-year construction of the smelter ensures that when the Tennessee furnaces finally ignite, the flow of raw materials from South America will be ready and unopposed by any Eastern competition.